Food Was Love, Security, and the Only Acceptable Vice: Understanding My Emotional Eating Story

You might think that because I just wrote two essays on food, eating, nutrition, and emotional and mental health, I have this area of my life well in hand. The truth is sometimes I do and sometimes I don’t. Our relationships with food are complicated. Here’s the story of mine.

The Chocolate Shoppe in Madison makes my favorite ice cream of all time. "Nutritional Information? Don't even ask," their signs say. Many summers ago, only one of their 100 flavors mattered to me: Zanzibar Chocolate. I would bike across town for it, drive out of my way for it, couldn't pass their downtown location without getting some.

"Some" meant two scoops, but at The Chocolate Shoppe, that's actually four massive scoops precariously perched on a sugar cone. One hot evening, sitting on State Street in the golden light of sunset, a tall, curvaceous woman sauntered by and shouted, "Lick those big, black balls!" For one awful moment, I froze, the hot flush of embarrassment creeping up my neck. I was suddenly, acutely aware of what I looked like: oblivious to anyone around me, a slight air of desperation, and focused entirely on eating this giant heap of ice cream without losing a single drop (a delightful challenge in the height of summer).

I wondered what I should do. Act like I’m in on the joke? Find somewhere to hide?

My self-consciousness and indecision didn’t last long, though. The woman laughed and rejoined her friends; dark brown rivulets of ice cream had begun oozing down the cone and dripping onto my fingers. In the end I didn't really care. I had work to do.

That ice cream wasn't just a sweet treat—it was filling a void that had nothing to do with hunger and everything to do with loneliness, heartbreak, and the absence of touch and connection in my life. As both a therapist and someone who has struggled with emotional eating my entire adult life, I've learned that our relationships with food are rarely just about food. They're stories about love, security, comfort, and the creative ways we learned to meet our needs when other sources weren't available.

When Food Becomes the Acceptable Vice

Growing up in a fundamentalist Baptist household, the rules were clear: no drinking, smoking, cursing or taking the Lord’s name in vain, playing cards, dancing, or going to movies. Sex is wrong unless you’re married; masturbation is dirty; a good woman is a selfless and submissive one; do what you’re told; behave or you’ll wish you had.

But there was one indulgence that escaped condemnation: food.

Our family holidays revolved around enormous spreads of homemade dishes. Everyone would bring something, and several of the women in my family had specialities that everyone looked forward to, some of which my mom refused to make because they were full of artificial colors and flavors. Even now as I write this, I have a visceral memory of my 10-year-old self looking at colorful, quivering Jello salads lined up on the kitchen counter, eyes wide and heart full of joyful anticipation.

I also have a vivid memory of watching Grandma at Christmas, walking back from the buffet with her plate heaped with food. Gluttony is actually one of the seven deadly sins according to Catholic theology but we were Baptist. Even so, any direct mention of gluttony in the Bible (Proverbs 23:20-21) was conveniently forgotten, especially during celebrations. Food became the one area where excess wasn't just permitted—it was encouraged.

Food as Love and Security

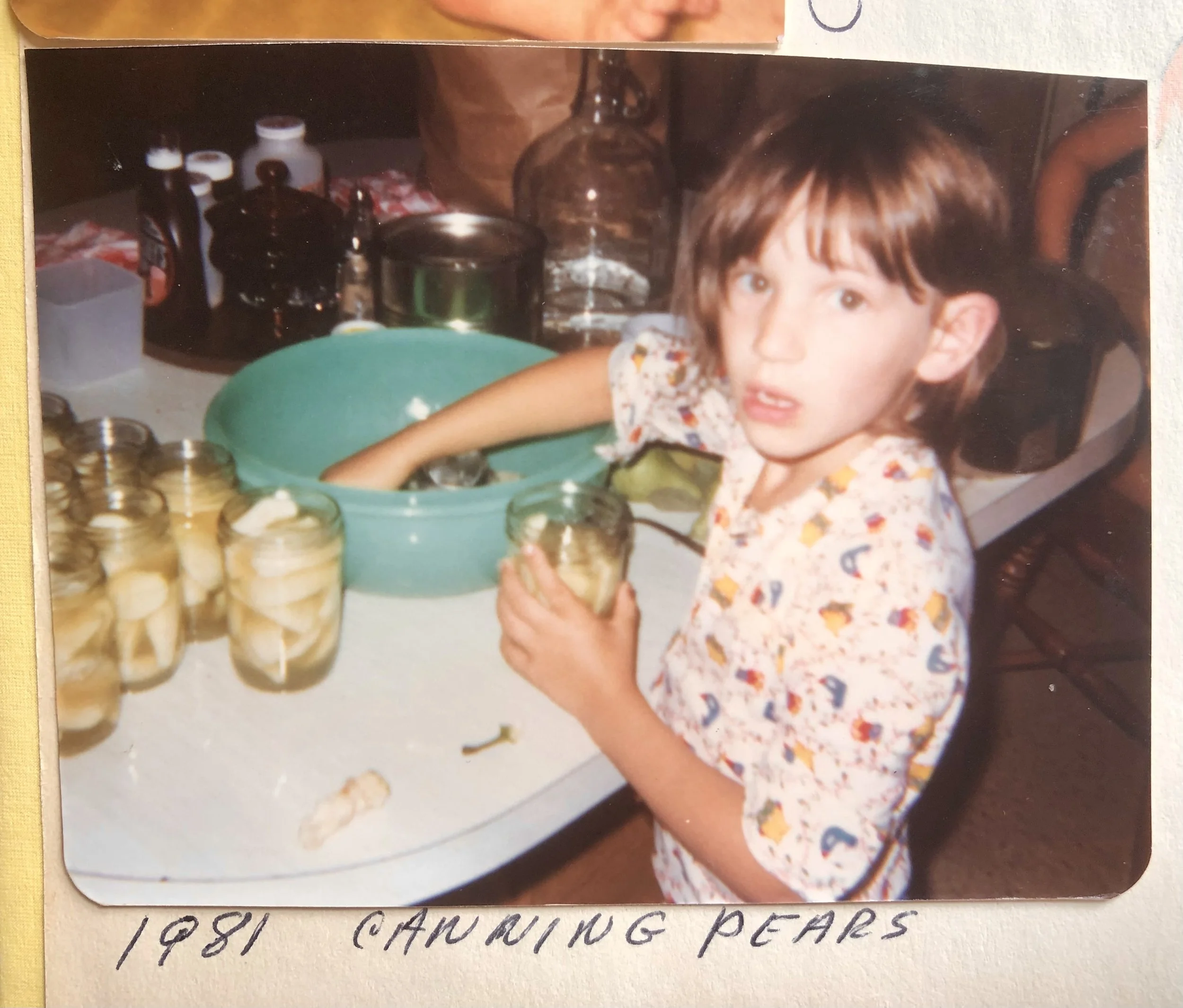

But food wasn't just about indulgence in my family—it was also a love language. My mother expressed her care and creativity through cooking and baking. She and my father cultivated an enormous garden, and my childhood summers were structured around food preservation: freezing corn, canning green beans and peaches, shucking peas, making dill pickles.

This rhythm of growing, harvesting, preserving, and storing food gave me a deep sense of abundance and security. I grew up poor. We didn’t have a working furnace or health insurance, but we always had enough to eat and it was homegrown and homemade. Walking into our pantry lined with colorful jars and our deep freezer packed with vegetables felt like visiting a treasure room. Food meant "we have enough"—perhaps the only area of life where that felt truly secure.

The Wisdom Behind Emotional Eating

As a therapist, I've learned to look for the wisdom in seemingly problematic patterns, and emotional eating is no exception. When I trace my own relationship with food back to its origins, I see a child who learned brilliant adaptations to her environment.

Food was available when other comforts weren't. It was culturally sanctioned when other pleasures were forbidden. It represented the deepest expressions of love and care in my family. It provided security in an otherwise uncertain world. That little girl who learned to associate food with comfort, celebration, love, and safety wasn't doing anything wrong. She was being remarkably intelligent about meeting her needs within the constraints of her world.

The challenge comes when childhood adaptations persist into adult life in ways that harm or actively work against us. At fifty, I’m still untangling this complex relationship with eating and I can't eat like I used to without physical consequences on top of the shame and regret. Fortunately I also have access to sources of comfort, pleasure, and connection that weren't available in my restricted childhood environment. But those early neural pathways are still there, still whispering that food is the answer when I'm lonely, bored, stressed, or avoiding something difficult.

The Sensuality of Substitute Connection

That summer of Zanzibar Chocolate obsession was a particularly lonely time in my life. I was single, not by choice, nursing a broken heart and missing human connection. Looking back, I can see how that rich, indulgent ice cream was meeting multiple needs: it was sensual pleasure when I was touch-starved, it was reliable comfort when relationship felt unpredictable, and it was entirely within my control when so much of my emotional life felt chaotic.

That ice cream ritual—the bike ride anticipation, the careful navigation of melting chocolate, the pure indulgence of texture and flavor—was genuinely nourishing in ways that went beyond calories. It was a creative attempt to meet legitimate needs for pleasure, comfort, and sensory satisfaction.

The problem wasn't the emotional eating itself—it was that I was trying to use food to meet needs that ultimately required human connection and emotional processing. No amount of Zanzibar Chocolate could actually cure loneliness, but it could provide temporary relief and genuine moments of pleasure while I worked toward meeting those deeper needs in other ways.

Learning to Recognize the Real Hunger

One of the most valuable skills I've been able to nurture is learning to distinguish between physical hunger and emotional hunger. They can feel remarkably similar, especially when we've been using food to meet emotional needs for years.

Physical hunger tends to develop gradually and can be satisfied by various foods. Emotional hunger often feels urgent and specific—it wants that particular ice cream, that exact comfort food, that specific taste or texture. Physical hunger is patient; emotional hunger feels demanding. With emotional hunger, the satisfaction is fleeting, sometimes only lasting for the time the food is actively being eaten.

But emotional hunger isn't wrong or bad. It's information. When I notice myself craving something specific that has nothing to do with physical nourishment, I try to pause and ask: What am I really wanting right now? Rest? Soothing? Connection? Variety? Pleasure?

Sometimes the answer is still food, and that's okay. But often, I discover I'm seeking something else entirely—a conversation, a walk outside, saying no to something I really don’t want to do, or simply permission to feel whatever emotion I'm experiencing without trying to change it.

But let’s be real: don’t imagine for one second that I have conquered this. It’s an ongoing practice and will be for the rest of my life. Perfection isn’t possible. What is possible is consistently choosing to refocus, as many times as necessary, on what my body and heart actually need.

Honoring the Complexity

Today, my relationship with food continues to evolve. I still love The Chocolate Shoppe's ice cream, though I haven't had Zanzibar Chocolate for years. I still eat when I'm not physically hungry, especially when I'm stressed or avoiding something. But I try to do it with awareness and self-compassion rather than self-criticism. Sometimes I’m able to make a different choice and sometimes I’m not.

There is no finish line; healing is an ongoing, dynamic process of acceptance and developing a kinder, more conscious relationship with food and with myself. It means honoring the wisdom behind my emotional eating while also expanding my capacity to meet emotional needs in other ways. It means recognizing that food was love, security, and comfort in my childhood, and while it can still serve those functions, I now also have access to many other sources of nourishment.

Moving Forward with Compassion

If you struggle with emotional eating, please be gentle with yourself.

Your relationship with food carries the story of your attempts to care for yourself, to meet genuine needs for comfort, pleasure, connection and security when other sources weren't available or reliable. That story deserves compassion and curiosity. And from that place of understanding and kindness, real change becomes possible.

Our relationships with food are incredibly complex and deeply personal. They're shaped by our earliest experiences of love, safety, scarcity, and abundance. They're influenced by cultural messages, family dynamics, trauma, and the countless ways we've learned to navigate a complicated world.

The work continues, one moment of awareness at a time, with as much grace and patience as we can muster.